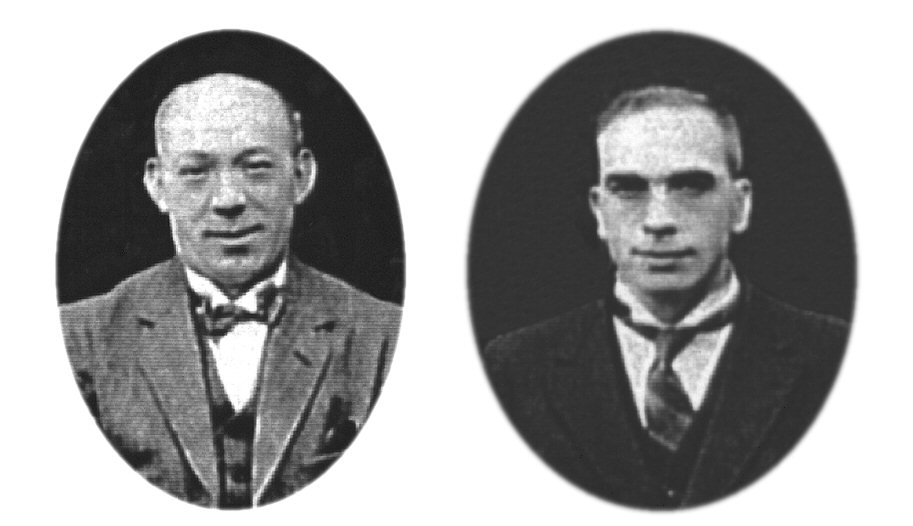

(Killed in the Attack)

The Irish ‘troubles’ have been stalking the people of Britain for over two hundred years, but nothing could have prepared the citizens of Glasgow for the events that unfolded in the streets of the City on a sunny afternoon in May 1921.

The Easter Rising in 1916 had sparked an explosion of violence in Dublin and beyond, but after the rebellion was suppressed, the Irish Republican Army brought a network of supply routes into use to bring arms, ammunition and explosives ‘across the water’. One of the centres of supply was Glasgow and some members of the predominantly Irish population of the east-end of the City were asked, cajoled and intimidated into storing the contraband in their houses, cellars and workplaces. The facility to store and onwardly transport such material was a key element in the well- oiled I.R.A. machine.

The Glasgow Brigade of the I.R.A. did not have it all their own way. The Glasgow Police had been gathering intelligence since before the start of the First World War and had succeeded in getting a number of specially selected men – not members of the force – into the I.R.A. These informers, together with the intelligence work of Detective Chief Inspector John McGimpsey of the Special Branch, had provided a mass of information. Such was the quality of his information gathering; D.C.I. McGimpsey was awarded the King’s Police Medal in 1919 for his secret work.

The person who caused the two sides, who had been spying on each other for years, to clash in the spring of 1921, was Frank T. Carty alias Frank Somers.

Carty was 32 years of age, an I.R.A. guerrilla fighter and friend of Michael Collins. He had been involved in armed conflict in almost every county in Ireland. Twice he had been caught, and twice he had escaped from the jails, in Sligo and Londonderry. It was after escaping from Londonderry in February, 1921, that he came to Glasgow. He thought he could hideout in Glasgow while providing his organisational skills to the supply route, based on his fighting experience. However, it was not long before the Glasgow Police intelligence network located him and he was arrested on 28 April 1921 for prison breaking and possession of a revolver. This caused serious consternation in the Glasgow I.R.A and they vowed to rescue him at all costs, before he was sent back to Ireland.

The leadership of the I.R.A. felt that, rather than trying to rescue Carty from police custody in Glasgow, their own plan of waiting until he was being transported back to Ireland was the preferred option. They would overcome the officers guarding Carty on the Irish ferry and take him back to Ireland in a fishing boat. A senior I.R.A. officer visited Glasgow after Carty’s arrest and instructed his Glasgow volunteers not to attempt a rescue, but they felt embarrassed for the lack of security that lead to Carty’s arrest and wanted to make amends in the eyes of their Irish commanders.

On Wednesday, 4 May, 1921, Frank Carty appeared at the Central Police Court, Turnbull Street, Glasgow, charged with the theft of a revolver and jail-breaking in Sligo and Londonderry.

Lieutenant Gray explained to the Court that the Glasgow Police had not received the case papers from Ireland and requested that Carty be remanded in custody in Duke Street Prison until Saturday, 7 May, so that the case against him could be prepared. The Magistrate granted the request.

Special precautions were taken, as the Glasgow Police knew they had a prisoner of particular importance in the I.R.A. movement.

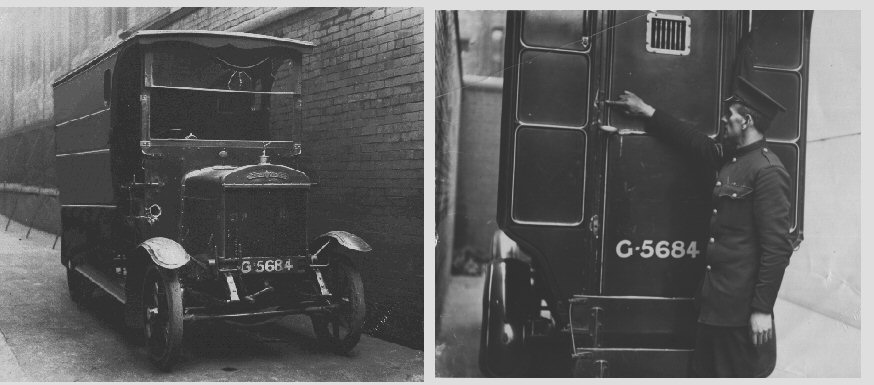

Detective Sergeant Stirton and Detective Constable Murdoch McDonald were armed with automatic pistols and took their place in the front of the prison-van alongside Inspector Johnston and the van-driver, Constable Ross. Shortly before 12.30 pm, the prison-van with Carty, another prisoner and two constables (PCs. Brown and Bernard), in the rear locked compartments, left the Central Police Office in St. Andrew’s Square. It continued up High Street towards Drygate, and the entrance to Duke Street Prison. The officers saw nothing suspicious at that time.

(Shot) (Van Driver)

When the prison-van had almost reached the prison gate, opposite Rottenrow, a fusillade of shots rang out, and the officers in the front of the van saw that they were surrounded by about thirteen men, in three groups, firing a variety of weapons at them.

Almost at once, Inspector Johnston collapsed onto the street, mortally wounded and D.S. Stirton and D.C. McDonald jumped out of the van and started firing at the attackers.

D.S. Stirton stood astride the body of Inspector Johnston, and continued firing until a bullet shattered his right wrist. D.C. McDonald fired at the attackers, dispersing them but then heard firing from behind him. When he went to the rear of the van he found two armed men working at the door trying to open it. When they saw DC McDonald approach them, they ran away and he chased them down High Street, but lost them. The door had withstood the attack and the van was driven into the prison without further incident.

Inspector Johnston was laid in a passing bakery van and taken to the nearby Royal Infirmary where he was found to be dead. He was 42 years of age and had served in the Glasgow Police for 19 years. He was buried at Balmaghie Churchyard, Galloway, on Saturday 7 May 1921 leaving a widow and two sons. D.S. Stirton later received medical attention to wounds to his wrist and upper arm. DC McDonald was uninjured.

Following the attack on the van and the murder of Inspector Johnston, the C.I.D. utilised their extensive criminal intelligence and a number of arrests were made in the east-end of the City. The police were mobbed when they arrested three priests at St. Mary’s Presbytery House, Abercromby Street. One was detained and the other two released following enquiries. Bottles and stones were thrown and the mob ‘laid siege’ to the Eastern Police Office in Tobago Street, until they were dispersed by reinforcements from the Central Police Office. A further nine individuals were arrested in connection with the murder. Numerous arrests were also made for Breach of the Peace and Attempting to Rescue Prisoners, and they all appeared at the Central Police Court the next day. A total of 34 persons were arrested, mostly found in possession of firearms and ammunition. A large amount of firearms, ammunition, explosives were also recovered. Carty was subsequently returned to Ireland to face charges there, without further incident.

Of the 34 persons originally charged, only 13 men were sent to the Edinburgh High Court for trial. All the accused pleaded ‘Not Guilty’ and the trial opened on 8th. August 1921, before the Lord Justice Clerk and a jury of seven men and eight women. The Solicitor General conducted the case for the Crown.

The case for the Crown mainly rested on identification and D.S. Stirton and D.C. McDonald were subjected to a gruelling cross-examination by the defence counsel. Against this the defence produced witnesses to prove alibi for each of the accused and alleged irregularities in police identification of the accused. The trial lasted eleven days and ended with the jury accepting the alibis given by the accused. Six of the accused were found ‘Not Guilty’ and the others ‘Not Proven’.

Recent research has established that in later years, some of the accused applied for pensions from the Irish Government as freedom fighters and made statements outlining their participation in the outrage.

During the investigation, Detective Superintendent Andrew Nisbet Keith received a letter from the Glasgow Brigade of the I.R.A. warning him that if he did not stop searching the houses of the Irish people of Glasgow, he would be shot. The letter, (now on display in the Glasgow Police Museum), is in polite, matter of fact language ending with the melodramatic poem:

My Pen is bad,

My Ink is pale.

But my shots to youse

Will never fail.

The threats against Mr. Keith were never carried out and he went on to be Chief Constable of Lanarkshire, retiring in 1946.

Detective Sergeant Stirton continued in the Glasgow C.I.D. until 1936 when, having reached the rank of Detective Inspector, he retired on pension. Detective Constable McDonald later followed Andrew Nisbet Keith to Lanarkshire Constabulary where he served as Assistant Chief Constable, retiring in 1946.

There is no doubt that both DS Stirton and DC McDonald, having served in the Army in the First World War, displayed selfless bravery and devotion to duty in repelling the attack on the prison-van when outnumbered by more than six to one. Having researched the incident extensively, my admiration for these men is only exceeded by my incredulity that they were not awarded the King’s Police Medal for Gallantry. It is likely that this was due, in the main, to the highly political aspects of the case, but it does not absolve the Government of the day from failing to acknowledge the outstanding bravery of these two officers.

© GPHS 2005