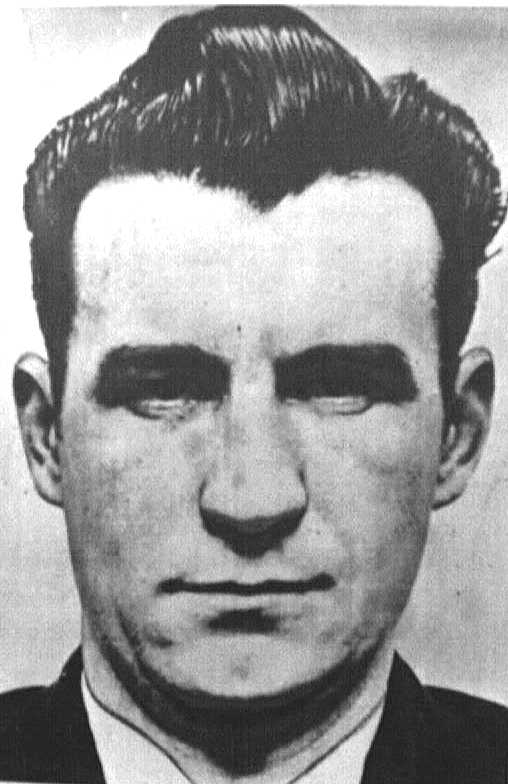

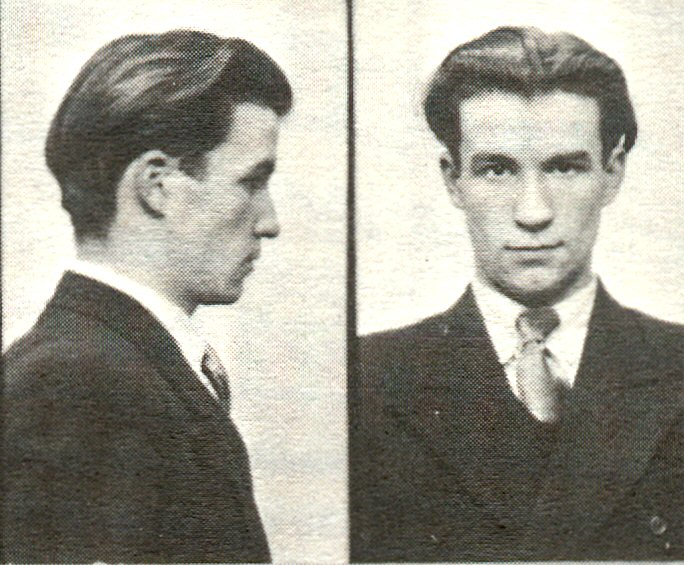

Perhaps the series of crimes most remembered and discussed by visitors to our Glasgow Police Museum, are the murders committed by Peter Manuel in the period 1956-57. Women, now in their sixties, vividly remember the fear they experienced during this time. Fathers or elder brothers met young women from evening buses and young people returning from a night out would band together to make sure they got home safely. This was the effect that Peter Manuel had on the people of Lanarkshire and eastern Glasgow during his two year reign of terror.

Peter Manuel was the second of three children to be born to Samuel and Bridget Manuel. Surprisingly, he was born in the Misere Cordia Hosptial in Manhattan, New York on 15 March 1927. His parents had emigrated to America to seek a better life during the Depression of the 1920’s. They tried to settle in Detroit, Michigan, with Samuel working in a car factory and Bridget working as a domestic servant, but Samuel became ill and poverty drove them back to Scotland in 1932. They were unsettled on their return and moved from Motherwell to Coventry in 1937. Peter was ten years of age and had an American accent. He did not settle into English school life.

Peter’s first brush with the law was in 1938 when he broke into a chapel and stole the offertory box. He was never out of trouble over the next few years and was a regular inmate of the borstals and approved schools. When he was 15 he committed his first act of violence when he attacked a sleeping woman with a hammer during one of his housebreaking ventures. For this he went to Leeds Prison. About this time his parents moved back to Lanarkshire after they lost their home to the bombing of Coventry, and Peter followed after he was released from borstal.

On 16 February 1946, Peter Manuel broke into a bungalow in the Sandyhills area of Lanarkshire. Detective Constable William Muncie (later ACC in Strathclyde Police) and a local sergeant searched the house and found a bedroom in the loft. Having satisfied themselves it was empty, they gathered the productions together and took them away for fingerprint examination.

Later that day, realising he had forgotten a cup in the kitchen of the house that appeared to have a fingerprint on it, D.C. Muncie returned to the house in time to see Manuel emerge from the garden. He apprehended him. He established that Manuel had been living in the house and had hidden behind wood panelling in the loft when the house was searched. While on bail for this offence, he committed three assaults on women, including a rape on an expectant mother. He got eight years imprisonment in Peterhead Prison and also won the praise of the judge for the skill with which he conducted his own defence! He was released in the summer of 1953, aged 26.

The afternoon of Wednesday 4 January 1956, was to mark the beginning of one of the largest police investigations Scotland has ever seen which would last for exactly two years. It was a cold, dry afternoon and George Gribbon was taking a walk on a golf course in East Kilbride when he found the body of a young woman in a wooded area known as Capelrig Copse. Sickened by the sight, Gribbon ran towards the road and saw some Gas Board engineers. His frantic description was taken as a joke by the workers and he ran off towards Calderglen Farm, from where he called the police.

The first officers at the scene found that the dead woman’s head had been smashed in. They also saw the marks of running feet in the mud which indicated that the woman had run for her life for over 400 yards. She had also been indecently assaulted.

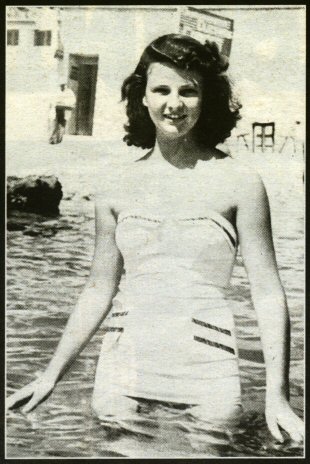

The woman was identified as Anne Kneilands, a 17 year old who had lived with her parents on the Calderwood Estate. She had gone dancing during the Hogmanay holiday on 2 January but had not returned. Her parents, thinking she was staying at a friend’s home, did not report her missing until the morning of 4 January.

The large investigation team was lead by Detective Chief Superintendent James Hendry of Lanarkshire CID and, from its early stages, Peter Manuel’s name was mentioned frequently. One instance of this was when Constable James Marr, on speaking to the foreman of the Gas Board gang, who had been working near where the body had been found, remarked that one of his workers, Peter Manuel, had been to prison for rape and had scratches on his face that were not there before 2 January. He was interviewed by Detective Chief Supt. Hendry but his father provided an alibi and further attempts to find evidence proved negative.

On 15 September 1956, police were called to a break-in at a home in Bothwell which bore all of Manuel’s hallmarks. Tins of food had been thrown onto the carpet and muddy boot marks were on the bedding. The next evening, there was a similar break-in at 18 Fennsbank Avenue, Burnside, and a quantity of cash and jewellery was taken. Again food tins were emptied onto the carpet and footprints were left on the bedding.

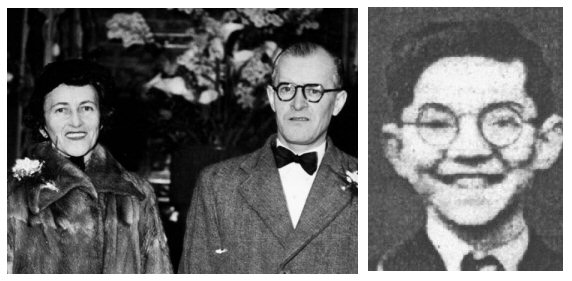

The next morning, 17 September, police were called to 5 Fennsbank Avenue, the house of the Watt family. William Watt was on a fishing holiday in Argyll, and left at home was his wife, Marion, his daughter Vivienne (aged 16) and his wife’s sister Margaret Brown.

The daily help, Helen Collinson, had arrived at the house to find the curtains pulled and a glass panel on the front door broken. When the police entered the house they found Marion Watt, Margaret Brown and Vivienne Watt shot dead in their beds. It was later established that a Webley service revolver had been the murder weapon.

The police investigation again included Peter Manuel and they obtained a search warrant for his parent’s house at 32 Fourth Street, Uddingston, but to no avail. Manuel also refused to speak to them and his father complained that the family were being victimised by the police.

The police also suspected that William Watt, a former War Reserve Policeman, may have been involved in the deaths. Extensive tests were carried out to verify if Watt had driven back to Glasgow overnight, murdered the women, then returned to Lochgilphead to complete his alibi. Whilst the results of most of the tests were inconclusive, a ferry master and another motorist identified Watt as having made the journey and both identified him in an identification parade. William Watt was arrested, charged with the three murders and held in Barlinnie Prison.

Whilst William Watt was in Barlinnie Prison, Manuel was also held there. Manuel sought out Watt and told him he knew who the real killer was. Lawrence Dowdall, Watt’s solicitor, also interviewed Manuel and was convinced that Manuel was the killer. Manuel was also interviewed by detectives, but refused to speak to them. After 67 days in custody, the case against William Watt had collapsed and he was released.

On Sunday 29 December 1957, William Cooke of Mount Vernon, Lanarkshire, reported his 17 year old daughter Isabelle missing to the police. She had gone to a dance the night before, but had not returned starting a frantic search by members of the family.

As part of the investigation, the police searched the River Calder and found one of Isabelle’s shoes and her handbag as well as other personal effects. Detective Inspector John Rae and Chief Inspector Muncie were among the senior officers investigating the girl’s disappearance. Detective Chief Supt. Hendry had retired on the very day Isabelle Cooke was reported missing.

On Monday 6 January, 1958, while Chief Inspector Muncie was leading a search of the area around a colliery air-shaft, he looked up to see Chief Constable John Wilson of Lanarkshire standing beside him. To his horror, Mr. Wilson told him that three people had been found shot in a bungalow in Uddingston.

At this point, the Chief Constable of Lanarkshire requested the assistance of two senior detectives from the City of Glasgow Police and Detective Superintendent Alex Brown and Detective Inspector Tom Goodall were seconded to the enquiry.

The house at 38 Sheepburn Road, Uddingston, belonged to the Smart family. Peter Smart (45), his wife Doris and their 11 year old son Michael lived in the house and their bodies were found after Mr. Smart had failed to turn up to work that Monday morning.

All three had been shot through the head with a Beretta pistol at point blank range while they were sleeping. Enquiries with friends and unopened mail indicated that they had been dead for several days. There was also evidence from neighbours that during that time, curtains had been opened and closed and lights switched on and off. This indicated that the killer had remained in the house with the bodies or returned several times without being seen. Mr. Smart’s car had also been stolen and it was later established that Manuel, whilst driving the car, had offered a lift to a policeman.

Detective Chief Inspector Muncie was intrigued by these circumstances and remembered his arrest of Manuel in 1946 when he had slept in the loft of a house after breaking into it. Other evidence was accumulating against Manuel, but the final piece of the ‘jig-saw’ was that banknotes from the Smart household were found to have been spent by Manuel in local public houses. On 14 January 1958, Manuel was arrested and charged with the murder of the Smart family.

(Recovered from the River Clyde)

A search of Manuel’s parent’s home produced items stolen from a housebreaking in Mount Vernon and, as the items had been in Samuel Manuel’s room, he was arrested for reset of the items.

When Manuel heard of his father’s arrest he immediately asked for a meeting with Inspector Robert McNeill of the enquiry team. At 3pm on 15 January 1958, Inspector McNeill and Detective Inspector Tom Goodall entered Manuel’s cell and he offered the officers a deal. If his father was released, he would make a clean breast of the crimes and take the officers to where Isabelle Cooke was buried and the place where he threw the guns in the River Clyde. This began a long series of confessions by Manuel to the murder of Anne Knielands, the Watt and Smart families and Isabelle Cooke. Eight murders which would make him Scotland’s most prolific mass murderer. He was also the prime suspect in the murder of a Newcastle taxi driver, Sydney Dunn, on 8 December 1957, while in the town for a job interview.

The trial of Peter Manuel which opened at Glasgow High Court on Monday 12 May 1958, was to last fourteen days and is one of the most documented trials in the history of the Scottish Criminal Justice system. Not only was the trial surprisingly short by modern standards, but it took the jury only two hours and twenty-one minutes of deliberations to convict him. He was sentenced to death at 4.45pm on 26 May 1958 which, after a failed appeal, was carried out at 8am on 11 July 1958.

There were few members of the public who mourned the death of Peter Manuel. Certainly, many families slept easier in their beds and young people relaxed on their evenings out, particularly in the Lanarkshire area, after Manuel was arrested.

(Glasgow) (Lanarkshire) (Glasgow) (Lanarkshire)

The Lanarkshire and Glasgow detectives who had banded together to solve these horrific murders could be justly proud of their work.

© GPHS 2005