Crimes motivated by political beliefs have been with us for thousands of years. Unfortunately, today most of these types of crime are known for their ferocity and needless violence, but one of the most bizarre political ‘crimes’ of the Twentieth Century was a removal of property which took place in London and was, in the main part, investigated by the City of Glasgow Police.

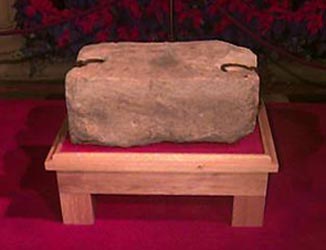

The object of attention was the Stone of Destiny, sometimes called The Stone of Scone, which is a block of sandstone measuring 40 centimetres wide, 66 centimetres long, 28 centimetres high and weighs 152 kg. It has two large metal rings set into it.

This plain block of Stone, built into the seat of the Coronation Throne in Westminster Abbey, has been revered as a holy relic for centuries, fought over by nations and used successively by Dalriadic, Scottish, English and British monarchs as an important part of their coronation ceremonies. Legend has it that this block of sandstone was originally used in biblical times by Jacob as a pillow. It is believed that it came to Scotland via Egypt, Spain and Ireland and was last used in a coronation in Scotland in 1292, when John Balliol was proclaimed King (although geological tests have found that it may have been quarried near Scone, Perthshire). Four years later, in 1296, the English monarch, Edward I (infamous as the “hammer of the Scots,” and nemesis of Scottish national hero William Wallace) invaded Scotland.

with Stone

Among the booty that Edward’s army removed was the legendary Stone, which the English king regarded as an important symbol of Scottish sovereignty. The present Coronation Throne was made to house the Stone in 1301.

From this provenance and the historical circumstances of its removal from Scotland, you would be forgiven from thinking that the Stone was, and still is, a symbol of Scottish sovereignty and the focus of Scottish nationalistic fervor. It is therefore not surprising that in the autumn of 1950, some politically astute academics were planning a publicity coup that would catapult their cause onto the front pages of newspapers across the World.

The members of the group were four enthusiastic Scottish nationalists, Ian Hamilton, Gavin Vernon, Kay Matheson and Alan Stuart. They were all members of the Scottish Covenant Association, a break-away group formed with the aim of a devolved Scottish assembly, rather than outright independence, the political cornerstone of the Scottish National Party. Hamilton, the 25 year old son of a Paisley tailor, was a law student at Glasgow University. Vernon was a 24 years old engineering student, also at Glasgow University, and a native of Aberdeenshire. The third member of the group, and the sole woman involved, was Kay Matheson a 22 year old trainee school teacher. Lastly, a man known only as Alan Stuart made up the quorum of conspirators.

The group set off for London on 22 December 1950 and on Christmas Eve, Hamilton, Vernon and Stuart entered Westminster Abbey as visitors and secreted themselves in one of the chapels until the building was closed following the traditional ‘Watch-Night’ service.

Kay Matheson waited nearby in the borrowed Ford Anglia motor car which was to transport the Stone and her accomplices away from the scene, but all was not going well inside the church. Hamilton, Vernon and Stuart made their way to the Coronation Chair which held the sacred Stone behind a grille below the seat. As the three men tried to access the Stone, they damaged the wood around the grille and as they removed it, the Stone broke into two pieces. They hurriedly carried the pieces to the waiting car and loaded them into the boot. As they were about to drive off, Hamilton saw that they had left the Abbey door open. He and Stuart returned to the door to secure it just as a beat constable appeared on the scene. They quickly hid inside and held the door, while Matheson and Vernon pretended to be a courting couple in the car. The beat officer checked the door and, satisfied, continued on his way. Hamilton and Stuart then reappeared, secured the door as best as they could, and leapt into the car which drove off at speed.

This was the first time in 300 years that the Stone had left the Abbey. On that occasion, in 1657, it had been taken to Westminster Hall for the installation of Oliver Cromwell as Lord Protector. So you can imagine the disbelief engendered when the details of the crime were circulated throughout the Establishment in London. The famed Scotland Yard detectives of the Metropolitan Police were soon on the case, but the Stone and the culprits had disappeared, leaving few, if any, clues. Due to the obvious ‘Scottish Connection’ to the case, they alerted, amongst others, The Chief Constable of Glasgow, passing on details of the crime. Chief Constable Malcolm McCulloch directed Detective Inspector William Kerr, Head of the Special Branch of the Glasgow C.I.D., to establish if any Glaswegians were involved.

It is believed that the Stone was secreted in the corner of a field in Kent for a few days and then, risking road blocks at the Border, the broken Stone was brought to Scotland. When it arrived in Glasgow, Baillie Robert Gray, who owned a Stonemason company, was given the Stone to repair. Gray was a founder member of the Scottish National Party and was, to say the least, sympathetic to the cause.

During the night of 28 December, the night watchman in Gray’s yard tripped over an unusual Stone with a ring at each end. He reported it the following day, after seeing a photograph of the stolen Stone in a newspaper, but by the time the police arrived, the Stone was gone. It was later alleged that after repair, the Stone was carried around Glasgow in a lorry and shown to sympathetic members of the Scottish Covenant Association and other like minded people.

Enquiries by the various police forces in Scotland were proving fruitless although rumours and counter-rumours were circulating. Detective Chief Inspector McGrath of Scotland Yard and another colleague came to Scotland and lodged in the Whitburn Police Training School, centrally located for them to be available to visit the key areas of the investigation, Edinburgh and Glasgow. However, Detective Inspector Kerr realised that such a mystery would require particular knowledge of the Stone and the Abbey. Knowing that the one place that would have this information was The Mitchell Library in Glasgow, he made enquiries there and discovered from their records that one man had recently been studying all the available books about the subject. Discreet enquiries revealed that the man, Ian Hamilton, had been missing from his usual haunts at the time of the theft of the Stone. He continued his enquiries, building up a picture of the suspected conspiracy involving the other participants, although he knew that what he had was only flimsy circumstantial evidence.

While Detective Inspector Kerr was diligently piecing the circumstances together, the story was never far from the front pages of the newspapers. It was well known that King George VI was ill with suspected cancer. Speculation was rife that if he died, the Stone would not be available to be part of the Coronation Ceremony and the legality of such a ceremony was being questioned. Such an eventuality was beginning to alter the popular perception of the theft of the Stone. With the King’s illness being openly discussed, the opinion of the Scottish public, who had initially seen the Stone’s removal as a daring swipe at the ‘English Establishment’ and a bit of an adventure, was now changing and the nationalists were rapidly loosing public support.

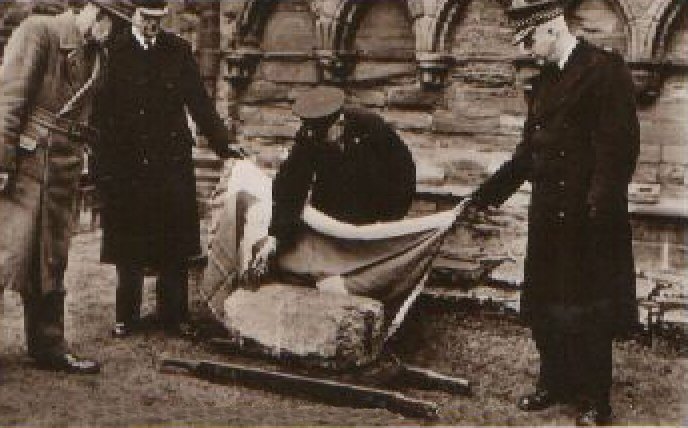

No doubt as a result of the waning public support, the conspirators symbolically left the Stone in Arbroath Abbey on Tuesday 10 April, 1951, where the formal Declaration of Scottish Independence had been drawn up in 1320. Newspapers carried banner headlines that the Stone had been found, but there was no claim of responsibility for ‘liberating the Stone’ by any of the nationalist organisations.

On that Tuesday evening, the Stone was brought to Glasgow under police escort and lodged in the office of the Head of Glasgow C.I.D. at the Central Police Office, Turnbull Street. Assistant Chief Constable James Robertson (later the City’s Chief Constable) took personal charge of the Stone and the following morning it was positively identified as the genuine Stone of Destiny by an official of Her Majesty’s Office of Works, the organisation responsible for the Stone at Westminster Abbey.

There was intense newspaper interest in the Stone and the Central Police Office was surrounded by the Press who had wireless cars waiting to follow any police cars carrying the Stone to London. The possibility also remained that students or other groups might attempt to re-take the Stone for publicity or other purposes. The Glasgow Police were determined that their planning would avoid such an embarrassing possibility.

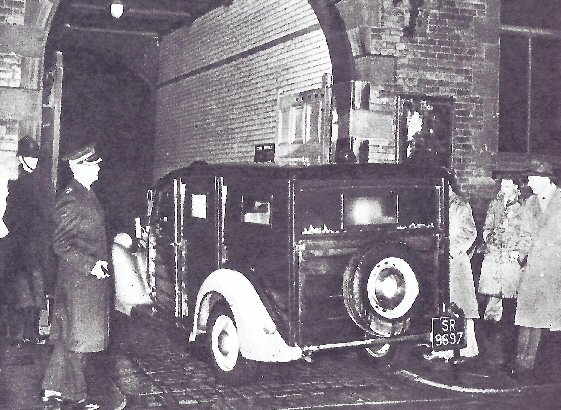

On Thursday, 12 April, 1951, instructions came from London requesting that the Stone should be transported there without attracting public attention, apparently oblivious to the intense newspaper coverage that the recovery of the Stone had already attracted. Arrangements were then made to have a large limousine brought into the quadrangle of the Central Police Office that evening. The plan was to transport the Stone in the limousine on Friday morning with a police Jaguar escort car, via Whitburn to pick up the two Scotland Yard detectives, then south to London. This seemed a reasonable plan but it had to be reconsidered overnight when information was received that a group of Scottish Nationalists from Glasgow and Edinburgh, some of them armed, were planning to prevent the Stone being removed from Scotland. However dramatically exaggerated this information may sound such a confrontation had to be avoided at all costs.

During the night the possibility of carrying the Stone in the Jaguar was discussed and, when measured, it was found that the Stone would fit in the boot with only fifteen centimetres (half an inch) to spare. To avoid the possible Nationalist roadblocks was essential, so an unusual route out of Scotland had to be carefully planned. It was also necessary to shake off the Press as a wireless car could be used to notify nationalist sympathisers of the location of the car carrying the Stone. The Press were expecting a ruse, so the Glasgow Police decided to give them one.

The new police plan was put into action at 5.30am on Friday, 13 April, 1951, when Assistant Chief Constable Robertson instructed that the large gates to the quadrangle of the Central Police Office be closed. Knowing that the Press would be watching, a number of detectives gathered around the limousine in the yard and, at 5.17am, the gates were opened and the police Jaguar car carrying Detective Inspector William Kerr accelerated out of the yard and headed south. The Pressmen knew Mr. Kerr well and thought it was an obvious ruse. Refusing to ‘take the bait’, the newspapermen stood their ground waiting for the limousine. Little did they know that the Jaguar car did, in fact, contain the Stone and it followed a less obvious route to Newcastle, thus avoiding any possible roadblocks.

At 5.20am, the second part of the plan was put into action when the yard gates were opened again and the limousine, with a police car at the front and rear, emerged at speed and headed eastwards. The Press cars roared into life and fell in behind the three official cars. Such a cavalcade of cars speeding through Glasgow in the early hours attracted the attention of many people heading for work. Many of the Press cars kept up with the three speeding official cars and, on reaching the Whitburn Police Training School to pick up the two Scotland Yard detectives, they crowded around the limousine. With the two detectives aboard, the limousine sped off, much to the consternation of the newspaper men, many of whom were ‘caught napping’ and failed to get their cars up to speed to catch the limousine. The limousine made the rendezvous with the Jaguar containing the Stone at Newcastle and continued south to London without incident. News that the Stone had reached its destination was greeted with relief at Glasgow Police Headquarters and many of those involved were able to get some rest after guarding the Stone for over seventy-two hours.

When it was received back at Westminster Abbey, the Stone of Destiny was put into the vault where it had been stored during the Second World War, until new security arrangements could be put in place for its safety under the Coronation Chair. It was replaced under the Coronation Chair in April 1952, following the death of King George VI on 6 February of that year, and used in the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II on the 2nd June 1953. However, rumours have circulated over the years since the theft that the Stone returned to the Abbey is in fact a replica and that the original Stone is in hiding somewhere in Scotland.

The enquiries into the removal of the Stone did not result in the prosecution of the four conspirators. It was felt that embarrassment would have been caused to the Crown. One theory is that in order to prosecute Ian Hamilton and his co-conspirators for theft, the Crown would have to have proved ownership of the Stone. This would have been very difficult to do as it is well known that the Stone was stolen from Scotland by England’s King Edward I in 1296.

After graduating from university, Hamilton forged a highly successful legal career, and, ironically for a committed republican, became one of Scotland’s most prominent Queen’s Counsel. Gavin Vernon graduated in electrical engineering and emigrated to Canada in the 1960’s. He lived in British Columbia until his death in March 2004. Kay Matheson returned to Inverasdale and was a teacher in the local primary school until her retirement. She died on 6 July 2013. Alan Stuart pursued a career in business in Glasgow and died, aged 88, in 2019.

Detective Inspector William Kerr continued in Glasgow Police until 1 June 1956, when he was appointed Chief Constable of Dunbartonshire Constabulary. Having served as chief constable for over 10 years and making many organisational changes, he embarked on the project to introduce a helicopter to the force. On a helicopter test flight, it returned to a landing pad adjacent to Constabulary Headquarters. The inspecting officials left the aircraft, but Mr. Kerr walked to the rear and was struck by the tail rotor. He sustained massive injuries, lost an eye and was it was thought that he would not survive. However, he proved them wrong and, after a long period of recuperation, returned to work. He retired shortly after.

On July 3rd 1996 in the Houses of Parliament, John Major, the then Prime Minister, announced that the Stone of Destiny would be returned to Scotland that year, only returning to Westminster Abbey for coronations. On the evening of 13th November, 1996, the Stone was removed from the Chair by representatives of Historic Scotland and put in a specially made crate. It was transported by stretcher to stand in the Lantern of the Abbey overnight and was removed in silence to the waiting police escort early on the morning of 14th November, 1996, to make the long journey back to Scotland by road. It can now be seen in the Crown Room in Edinburgh Castle. So the Coronation Chair, once the oldest piece of furniture in England still used for the purpose for which it was originally built, now stands empty after 700 years.

On 24 December, 2020, the Scottish Government announced that the Stone would be moved from Edinburgh to a new museum which will open at Perth City Hall in 2024.

© GPHS 2006